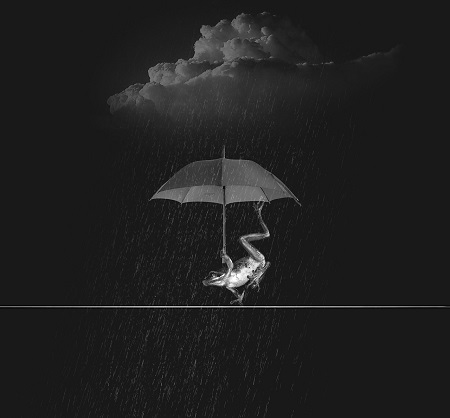

Rain Of Animals

Raining animals is a rare meteorological phenomenon in which flightless animals fall from the sky. Such occurrences have been reported in many countries throughout history. One hypothesis is that tornadic waterspouts sometimes pick up creatures such as fish or frogs, and carry them for up to several miles. However, this aspect of the phenomenon has never been witnessed by scientists.

animals is a rare meteorological phenomenon in which flightless animals fall from the sky. Such occurrences have been reported in many countries throughout history. One hypothesis is that tornadic waterspouts sometimes pick up creatures such as fish or frogs, and carry them for up to several miles. However, this aspect of the phenomenon has never been witnessed by scientists.

French physicist André-Marie Ampère (1775 – 1836) was among the first scientists to take accounts of raining animals seriously. Addressing the Society of Natural Sciences, Ampère suggested that at times frogs and toads roam the countryside in large numbers, and that violent winds could pick them up and carry them great distances.

Sometimes the animals survive the fall, suggesting the animals are dropped shortly after extraction. Several witnesses of raining frogs describe the animals as startled but healthy, and exhibiting relatively normal behavior shortly after the event. In some incidents, the animals are frozen to death or even completely encased in ice. There are examples where the product of the rain is not intact animals, but shredded body parts. Some cases occur just after storms having strong winds, especially during tornadoes. However, there have been many unconfirmed cases in which rainfalls of animals have occurred in fair weather and in the absence of strong winds or waterspouts.

A better accepted scientific explanation involves tornadic waterspouts: a tornado that forms over land and travels over the water. Under this hypothesis, a tornadic waterspout transports animals to relatively high altitudes, carrying them over large distances. This hypothesis appears supported by the type of animals in these rains: small and light, usually aquatic, and by the suggestion that the rain of animals is often preceded by a storm. However, the theory does not account for how all the animals involved in each individual incident would be from only one species, and not a group of similarly-sized animals from a single area. In the case of birds, storms may overcome a flock in flight, especially in times of migration. These events may occur easily with birds, which can get killed in flight, or stunned and then fall (unlike flightless creatures, which first have to be lifted into the air by an outside force). Sometimes this happens in large groups, for instance, the blackbirds falling from the sky in Beebe, Arkansas, United States on December 31, 2010. It is common for birds to become disoriented (for example, because of bad weather or fireworks) and collide with objects such as trees or buildings, killing them or stunning them into falling to their death. The number of blackbirds killed in Beebe is not spectacular considering the size of their congregations, which can be in the millions. The event in Beebe, however, captured the imagination and led to more reports in the media of birds falling from the sky across the globe, such as in Sweden and Italy, though many scientists claim such mass deaths are common occurrences but usually go unnoticed. In contrast, it is harder to find a plausible explanation for rains of terrestrial animals.

In the case of birds, storms may overcome a flock in flight, especially in times of migration. These events may occur easily with birds, which can get killed in flight, or stunned and then fall (unlike flightless creatures, which first have to be lifted into the air by an outside force). Sometimes this happens in large groups, for instance, the blackbirds falling from the sky in Beebe, Arkansas, United States on December 31, 2010. It is common for birds to become disoriented (for example, because of bad weather or fireworks) and collide with objects such as trees or buildings, killing them or stunning them into falling to their death. The number of blackbirds killed in Beebe is not spectacular considering the size of their congregations, which can be in the millions. The event in Beebe, however, captured the imagination and led to more reports in the media of birds falling from the sky across the globe, such as in Sweden and Italy, though many scientists claim such mass deaths are common occurrences but usually go unnoticed. In contrast, it is harder to find a plausible explanation for rains of terrestrial animals.

After a reported rain of fish in Singapore in 1861, French naturalist Francis de Laporte de Castelnau established that a migration of walking catfish had taken place. As these fish are capable of dragging themselves over land from one puddle to another, this accounted for their presence on the ground following the rain.

The English language idiom "It is raining cats and dogs" (referring to a heavy downpour) is of uncertain etymology; there is no evidence that it has any connection to the "raining animals" phenomenon.

Source: Rain Of Animals